- Home

- Amy P. Knight

Lost, Almost Page 9

Lost, Almost Read online

Page 9

Adam had always presented the projects—the combination of baking soda and vinegar to produce a bubbling froth, the construction of a homemade light bulb—as serious investigation. He gave Curtis a hard-bound lab notebook pilfered from work and taught him the art of record-keeping, always recording the date, the time, the location, the materials, always writing in ink. “This is one for the books,” he’d say, leading Curtis out to the garage where he kept stashes of chemicals, spare electrical parts, batteries, tools.

Angeline wasn’t sure that Curtis enjoyed these charades. He looked scared as he worked, and some Sunday nights, she heard him tossing in bed late into the night. She imagined him worrying about the outcomes of the crucial experiments in which he believed his father was relying on him. It was too much for such a young boy. She brought him watercolor paints and thick, smudgy sticks of charcoal. She talked to him about the books he was reading in school and offered to drive him to friends’ houses. She picked up the doodles he’d drawn in art class and praised them effusively. But if Adam was in the house, Curtis never seemed to hear her.

“Isn’t this is getting out of hand?” She would ask Adam when the two of them had climbed into bed, the desk lamp still on after nine in Curtis’s room down the hall. “He thinks he’s taking the world on his shoulders.”

“He’s learning the importance of inquiry,” Adam said. She turned toward him, but his eyes were locked somewhere far away. She knew his heart was in the right place, if he would ever admit to being guided by a heart, and it was true that she had no provable reason why her approach would be better, but she felt sure that she could convince him to go a little easier, that she should.

“He just wants to be around you,” she said, as gently as she could. “He wants a little attention.”

“I give him every Sunday.” Still, he did not face her. He sat very straight against the headboard, his legs straight out, his toes sticking up under the quilt, with a perfect stack of three pillows. “That’s more than Jim and Larry give their boys. Considerably more.”

“I think, love,” she said, “that he wants to know you think he’s all right.” She reached across the space between them and rested her hand gently on his forearm. He was in his nightshirt but still had his watch on.

“He is all right.” He shifted on the mattress and turned his head even farther away, his eyes cast now to the corner of the room. “His notes are more meticulous than mine are. Any lab in the country will be able to use a kid like this.”

“Tell him,” she said. And Adam would nod, but she’d never heard him offer that kind of praise. Not to anyone.

Curtis had not come home when she arrived back at the house. She tucked the envelope under one arm as she carried her two plastic grocery bags into the house. It fell on the floor as she settled the bags on the counter. She considered how the rest of the afternoon would go. Maybe she should put the letter back in the mailbox. She could tell Curtis she’d been too busy, or had been resting, and ask him to go out for the mail. Or she could put it back on the table and wait for him to see. She wished all the colleges had replied at once. He would be accepted, she was sure, at Columbia, too, and Chicago. She could have laid the choices out in front of him, looking for the moment like paths that were equally open to him. She could have pretended, they all could have, that he might choose somewhere else, a school where he might discover other interests, where he would be more likely to meet people of the sort he had never come across here in Los Alamos.

She held it flat on the palm of her hand, feeling its heft, the cool smoothness of the paper. It was then, with two lemons rolling around on her counter, that it occurred to her that she could save it for a day or two. More letters would surely come, and soon. Rather than give it to him now, all of them assuming and agreeing that the choice was made, she could, for a little while longer, imagine that he might be more independent, more like her. But she had already bought the ingredients for the lemon chicken. Surely, even if she did not prepare it, Curtis would notice the contents of the refrigerator.

Still, the thought of just another day or two with uncertainty, with possibility, was attractive. She could see her husband’s face, the mixture of smug I-told-you-so certainty and genuine pride that his son was so much like him, and she couldn’t bear it. She carried the envelope down the hall to her bedroom.

She slid open the top drawer of her chest and scooped out her underthings: stockings, camisoles, bras, panties. She laid the envelope smoothly along the bottom. She piled her things hastily back in and returned to the kitchen, her cheeks flushed. She checked the kitchen clock. It was just after three. She still had perhaps half an hour before Curtis arrived. He would hate it if he knew she had planned a celebration before the news had come; she was going to have to make it into no celebration at all, a diversion she had dreamed up for herself to pass the restless hours. She set to work immediately; it would have to be well underway if it was supposed to be a project undertaken for its own sake during the long, lonely afternoon.

Soon she was chopping onions, juicing lemons, preparing to marinate the chicken. The big knife had gone dull. She had to saw back and forth on the onion to break through the skin. Once, the knife slipped, and for a moment she was so sure she had sliced through her finger that she stared in disbelief at her dry, white hand, searching for blood.

She was pouring the batter for a loaf of soda bread into a greased pan when he came through the door, backpack slung over one shoulder.

“Any mail?” he said.

“Nothing yet, darling.” She hoped she sounded as she had on all the other days when she’d given the same answer. Curtis made a sound, a little cough. His face showed something more than the mild disappointment of waiting another day. “What’s wrong?” she asked. She could feel her pulse in her neck, and in her thumbs.

“Clark Anderson got his today,” Curtis said. “His mother called the school when the mailman came. Mrs. Ford came and got him out of class.”

“All the schools are a little different, Sweetie,” she said. “Just because one school mailed acceptances doesn’t mean—”

“No, Mom, it was Cal Tech. If I’d gotten in, it would have come today.” He kept his eyes down, and she felt a rush of sympathy. She knew how it felt to be too upset for eye contact, sure that what little composure was left to you would not withstand a moment’s personal connection.

“Well now,” she said, “the mail here has never been all that reliable.”

“I want to call Dad,” Curtis said. “I should tell him.”

“Now hang on,” Angeline said. “Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. There’s no reason to assume the worst.” Her throat ached. She let the loaf pan sit unbaked on the counter, the oven hot, ready. She took a deep breath and tried to think. She could bring an instant end to his suffering. But if she produced the envelope now, it would seem like a cruel prank she had played on him, and then the evening would unfold between Curtis and Adam, as a celebration of Curtis’s impending departure for Pasadena, and she couldn’t bear to see his center of gravity shift already from here to there. She needed another day or two, the survival of a slim hope that he might surprise them all.

“The post office is fine,” he said, his voice so soft it barely disturbed the air around him.

“No one is a better student than you,” she said. “And with your connections. I’m sure it will be here any day. Maybe they’re sending you a special letter, a special offer, and it took an extra day or two to put together.”

“Yeah,” he said, “maybe.”

“I’m making us a special dinner,” she said. “Just because I love you. Your favorite chicken.”

“I don’t want lemon chicken,” he said. “I want to go to Cal Tech.”

“I know you do, Baby,” she said. “Why don’t you get started on your homework. Take your mind off it. You want something to drink?” He didn’t answer her. He disappeared down the hall into his room, and a minute later she heard the opening chords of �

�Tax Man,” muffled by his closed door.

She put the bread into the oven. She was suddenly very tired. She sat in one of the hard kitchen chairs and rested her head in her hand. She hadn’t had a day this active since before her surgery, and she had worn herself out. The smell of the bread started to permeate the air. She wondered if Curtis was thinking about the other schools he had applied to, if he knew which was his next choice, if there was any part of him, even some secret, silenced part, that might be relieved. She didn’t imagine so; the sting of rejection would take a few days to give way to planning, and by then she’d have slipped the letter back in among the rest of the mail. “Tax Man” turned into “Eleanor Rigby.” She wanted to lie down, but she didn’t want to be in the bedroom, with the letter. She moved to Adam’s easy chair in the living room and propped her feet on the ottoman. She closed her eyes, and dozed.

She didn’t like these long lonely days. All afternoon she had been waiting for Curtis, and now that part of the day had come and gone in the space of a few minutes, and she was waiting for Adam. Lots of women, she knew, lived their entire lives like this, their lives shaped by the comings and goings of men. They must have had their own ways of arranging their days so that they weren’t disappointed all the time. She wondered if this prospect was what had driven her own mother away. She had never before felt even a tiny grain of understanding of how she could have done it, disappeared, leaving a daughter who had not yet learned to walk, back to France without leaving so much as a photograph, trying for all the world to make it seem as though she had never been there.

But of course, she had been there, had loved a professor, or thought she had, had given birth to a restless daughter. And now Angeline herself felt that she was fading from the Earth, that her son might go off into the world stamped deeply, indelibly, with the marks of his father, like a newer, faster train along the same track that had been laid before he was born. And when he was gone, she, too, would vanish.

There had been one Sunday morning, during a particularly intense period in Adam’s work on the Test Ban Treaty, when he’d sequestered himself in his study shortly after dawn. Angeline wasn’t sure of the details, but she understood that Adam was trying to work out a very delicate deal, and she suspected that he was working outside of the rules, risking his own high position in hopes of preventing greater destruction. He had seen and imagined things she could not absorb. She was staying out of his way, nursing a cup of coffee and skimming the paper, when he burst into the hallway.

“Get away from here!” he roared. “You thought you’d eavesdrop on me? You want the FBI coming in here?” Curtis had been sitting, unobserved by either parent until that moment, outside the study door, waiting for his father to emerge and begin their usual Sunday time together. Instinctively, Angeline got to her feet and went to the doorway, where she could see Curtis shuffling backward toward his bedroom.

“I’m sorry,” Curtis said faintly.

“Sorry doesn’t mean anything!”

Curtis ran down the hall into his room, barely getting the door closed before he began to cry. Angeline knew better than to speak to Adam just then. She’d learned, through years of quiet observation, that more likely than not, he was afraid that he was in the midst of some monumental failure. He meant no harm. He had to be forgiven a slip of the temper here and there, with everything that he was trying to do. She went instead to Curtis’s room.

“He didn’t mean it, sweetie,” she said, standing in the doorway. “He was mad at the man on the phone, and he took it out on you.”

“I shouldn’t have been there,” Curtis said into his pillow. “I shouldn’t have listened.”

“Let’s do something just you and me. I’ll take you to town. Buy you a new comic.”

“Leave me alone,” Curtis said.

“I could take you over to the park and catch the baseball for you.” He didn’t answer. She stayed another minute, but he did not stir, and she withdrew. When she peeked in the door a few minutes later, he was hunched over a thick textbook, a gift from his father. Introductory Physics, Adam’s own text from his first year at Cal Tech. It was far too difficult for even the brightest of twelve-year-olds, but Curtis could not be torn away.

That afternoon, Adam had gone to make amends. Angeline had been out in the garden when most of it had happened, getting everything ready for the winter, but she’d pieced it together well enough. Remorse had caught up with Adam, and he had planned an experiment for them to do together, a good one, a real treat. He’d found Curtis in his room, deep in his studies.

“I need your help,” he said. Timidly, Curtis lifted his eyes but said nothing. “Know anything about sodium?”

“A member of the alkali family,” Curtis said, barely above a whisper. “Atomic number twelve. No, eleven. Twelve.”

“Eleven,” Adam said, much more gentle than he usually was in correcting Curtis. “I have an investigation to conduct. Think you can give me a hand?”

“You don’t want me,” Curtis said. “You want someone who doesn’t wait in the hall.”

“I want you,” Adam said. “You take the best notes.”

Together, they went out to the garage, where Adam took a big metal box from a high shelf. The box contained a large, silvery-white lump of metal, packed in oil, and several smaller pieces.

They brought it into the house. Adam took a pasta pot from the rack on the wall and filled it with several inches of water as Curtis recorded all the information he had so far: 12/5/68. Los Alamos, NM. Sample of elemental sodium, source unknown. His hand shook as he wrote, and he pressed harder to keep his letters even.

“What’s the research question?” Curtis asked.

“Just watch a minute.” Using a pair of Angeline’s kitchen tongs, he took the smallest piece of sodium, no bigger than a raisin, and dropped it into the pot. Immediately, it began to sizzle and whiz, skipping across the surface of the water, glowing hot. It banged against the metal sides of the pot and sputtered and burned until it sank, reduced to a pebble of ash, and came to rest on the bottom.

“I see,” Curtis said. “We can use it as a fuel.”

“Exactly,” Adam said. “We’ll test some of these different pieces and see how they behave. That big one, though, we’ll have to take to Ashley Pond. When the chunks reach a certain size, they don’t just sizzle. They explode.”

Curtis’s eyes grew wide as he struggled for the proper response. “How are we going to measure the— the— the energy output?”

“So far, we’re just observing,” Adam said. “Once we get a sense of what we’re dealing with, we can design a more controlled experiment.” Curtis dropped the next piece in and watched it sizzle. Adam did the third one. The sodium whizzed and clanged and smoked and burned.

The fourth piece was bigger than the first few. “Stand back,” Adam warned. “This one might burn hotter.”

“That’s a good point,” Curtis said. “There’s no reason to assume a— a—” he struggled again for the words— “a linear correlation between size and energy output.”

“Attaboy,” Adam said. “Now stand back and let her rip.” Curtis dipped into the metal box with the tongs, took the lump of sodium, and stood back.

Angeline heard the bang from across the yard: as soon as it hit the water, the sodium broke into a dozen tiny pieces and flew, in a shower of sparks, out of the pasta pot and high up to the ceiling. She came running inside to find her husband and her son staring at each other, a thin smoke in the air. It only took her an instant to look up and see the damage they’d done.

It was with characteristic force that, shortly after six, Adam came through the door. He was forever moving faster, and with more power, than was necessary, propelling himself from the bed to the shower, out the bathroom door after washing his hands, as though he were used to living in a world of more gravity than this one.

She watched him take in the array of bowls and pans that she hadn’t yet cleaned. She could see his lightning-quick thought p

rocess. “News?” he asked.

“No news,” she said. “I just had to get up and do something. A project.”

“You’re feeling better?”

“Yes” she said, “a bit.”

“I’m glad to hear it.” He leaned in and kissed her on the forehead.

“What kind of day was it?” she asked. This was another reason she hated being trapped at home. When she was at work, she could usually tell the tone of his day, even though she was up one floor and at the other end of the hall. Now, this last week, the man who came through the door at the end of the day might be whistling, or might be barely able to lift his feet under all the weight he bore, work he was forbidden to discuss. She rubbed her temple. Her secret was nothing, she knew, a tiny deception, a burden of her own making. But she felt it there between them.

“An uneventful day,” he said. “On all fronts, it seems.”

When the three of them sat down to dinner, Angeline found herself without anything to say. Any mention of colleges would require a lie. The clinking of silverware grew heavy in the air. She considered turning on the radio for a newscast, but Adam didn’t like to listen to the news at home. It made him tense and irritable.

Finally, Curtis spoke. “Clark Anderson got into Cal Tech today. Mom thinks my letter is still coming. Delayed at the post office, or mailed separately. I think that’s unlikely.” He put a very large piece of chicken into his mouth and chewed intently. His eyes were fixed somewhere over Adam’s head.

“Today?” Adam said. “The letter came today?”

“His mother called the school.” Adam looked at Angeline for confirmation, or perhaps for some clue as to what all this meant. She pressed her lips together. He had been certain that Curtis would be swiftly admitted, more certain than the rest of them. He would know that something wasn’t right.

“Well,” Adam said at last, “I’m sure your mother’s right.”

“There’s more bread,” Angeline said. “Would anyone like more bread? I could make more salad if anyone—”

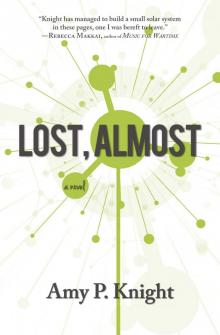

Lost, Almost

Lost, Almost